Solar panels are made from the Earth. It’s a part of our Mother who should be treated with reverence and care.

Those of us concerned about climate justice have to look very carefully at how the solar industry replicates old models of extraction. At the same time, we have to acknowledge that criticism of the industry is overstated — and largely built on fossil fuel industry’s talking points in their attempts to keep polluting at far greater rates. This is very short review.

Where are solar panels made?

Most of the assembly of solar panels happens in China (7 of 10 the biggest solar companies). The others are in US, South Korea, Canada, and Germany.

But that’s not really where they come from — just where their many parts are assembled.

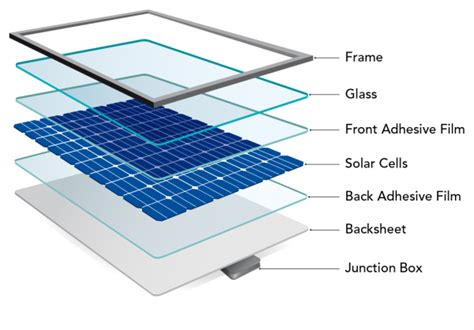

Where do the parts of a solar panel come from?

A critical piece in solar panels are the cells which are made from solar-grade polysilicon. Nearly half (45%) of that polysilicon is produced in the Uyghur Region in China. There is huge evidence that there the workers are forced laborers from the Uyghur population.

Most of the rest of the solar panels — like the frames — are typically from recycled aluminum or other reused materials (roughly 40%).

What about lithium and cobalt?

Batteries typically use lithium and cobalt (or other rare earth metals). The type of metal used differs depending on the type of battery. But based on current technology, there is a global race for these minerals because of the boom in solar batteries and storage.

Cobalt is largely produced in the Democratic Republic of Congo — two-thirds. Much of this is funded from China. In the Congo there are deep, ongoing abuses of human rights. Unlike in China, pro-human rights groups haven’t suggested a boycott from Congo would help; instead, there have been demands for solar companies to require their partners operate under human rights laws.

Lithium is found more scattered across the globe. The largest deposits are in Bolivia, Argentina, Chile, US, Australia and China. China has the most developed lithium mines and has largely cornered the market as of now. Accusations of forced labour at Chinese mines is rampant. The US, by contrast, has only one operating lithium mine — others are proposed in Native American sacred lands.

Generally, mining is a filthy industry. It produces tons of waste. Requires high use of water. Is associated with poor working conditions. Creates new geopolitical tensions. And it takes a lot of energy to mine.

Sounds awful. Are they that bad?

In my smalltown of Richmond, Indiana — a quiet town of 30,000 people — the fossil fuel industry sent along its talking points: “Wind turbines kill birds. Solar exploits human rights. They’re ugly and bad for the environment and people.” The city put a pause on all wind turbines.

The fossil fuel industry stands to lose a lot of money and power. They regularly build up attacks on solar. But it’s really, really, really important to remind ourselves all the things the fossil fuel industry has brought us:

- Wars over oil (like Iraq) and oil-funded wars (like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine)

- Brutal working conditions, including many of the same accusations leveled against solar

- Millions of people dying from air pollution

- …and of course climate devastation which threatens all of us!

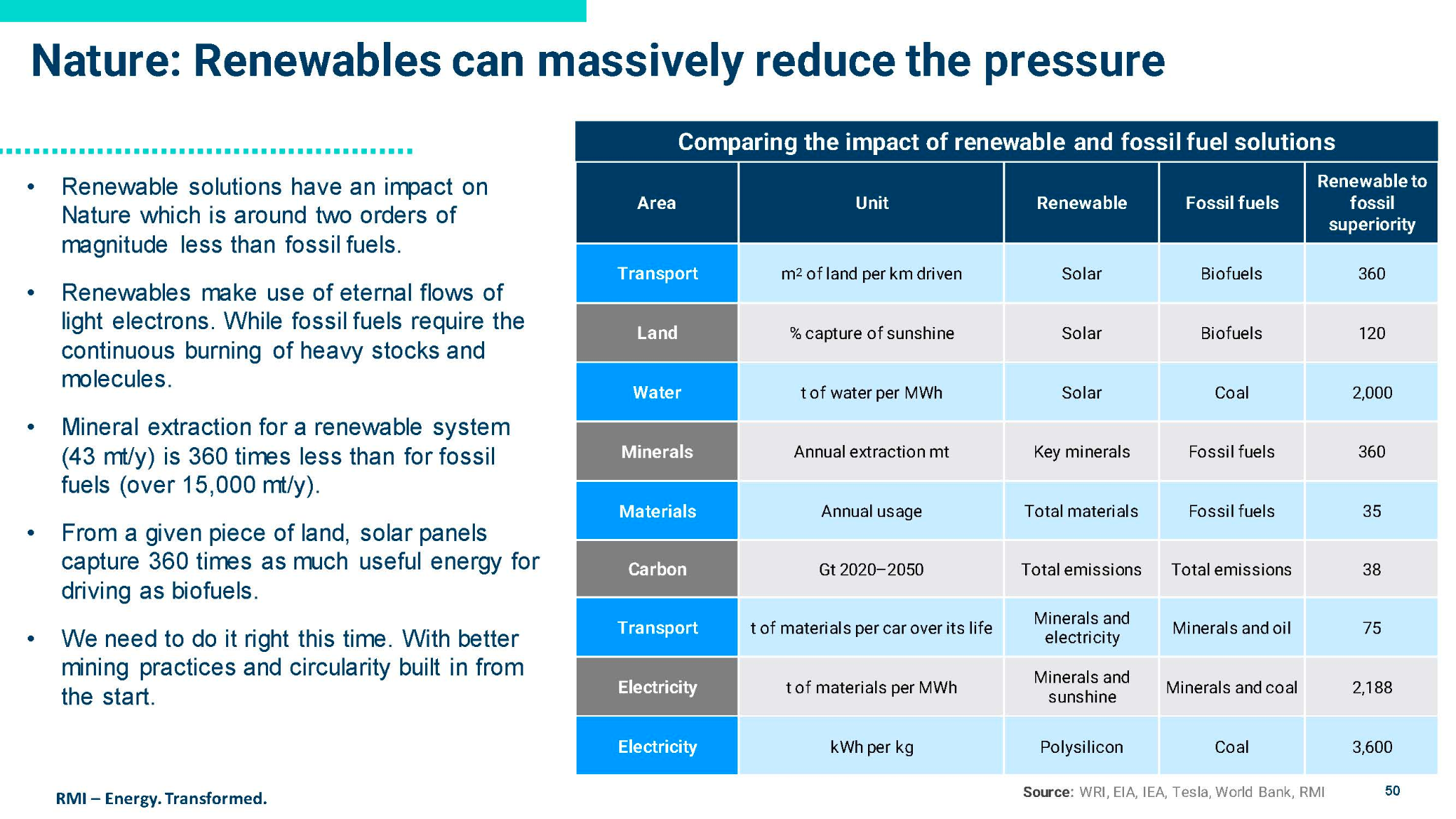

Comparing the levels of mining of solar to fossil fuels

Bill McKibben reminds us, “It’s worth remembering that a transition to renewable energy would, by some estimates, reduce the total global mining burden by as much as eighty per cent, because so much of what we dig up today is burned (and then we have to go dig up some more). You dig up lithium once, and put it to use for decades in a solar panel or battery. In fact, a switch to renewable energy will reduce the load on all kinds of systems. At the moment, roughly forty per cent of the cargo carried by ocean-going ships is coal, gas, oil, and wood pellets—a never-ending stream of vessels crammed full of stuff to burn. You need a ship to carry a wind turbine blade, too, if it’s coming from across the sea, but you only need it once. A solar panel or a windmill, once erected, stands for a quarter of a century or longer. The U.S. military is the world’s largest single consumer of fossil fuels, but seventy per cent of its logistical “lift capacity” is devoted solely to transporting the fossil fuels used to keep the military machine running.”

This report on the Renewable Energy Transition notes these numbers. Yes, lithium mining is bad — but doing it once is far less intensive than the constant churning mining of fossil fuels.

Key statistics here: mineral extraction for a renewable system is 360 times less than for fossil fuels.

But what about people impacted by solar mining? How to make this industry better?

While Gandhi was campaigning to get his country free from British rule, he saw other disenfranchised people suffering from his actions. His quest to make Indian clothing meant that textile workers back in the UK were losing jobs, often under harrowing conditions.

He made a trip to visit them. There he explained why he was calling for the boycott — even knowing it would harm them — while simultaneously calling for them to learn his techniques of nonviolent resistance from their oppressors (also the British government).

This was a solidarity move.

There are various moves underway to try to address and mitigate these negative impacts of the growing solar industry. We can play a role by joining our voices with them.

- Solidarity with frontline communities. Build relationships, swap tools of resistance, hear each other’s stories. In some cases, like China, there have been calls by human rights groups to stop all factories using forced migration and largely move out of places where human rights conditions cannot be confirmed. In Congo the calls have been more about upholding human rights and therefore using company’s powers to do that. In Nevada, Native communities have said loudly they do not want mines imposed on their sacred lands. Learning from the people on the ground helps nuance what is best to ask.

- Calling for more transparency in solar reporting so we can track where the parts are coming from and exposing human rights abuses. North American manufacturers are beginning to use the Solar Energy Industries Association’s Traceability Protocol. You can also read independent reports.

- Calling for solar panels to be made so they are easy to recycle — and setting up recycling centers. In a few decades we are going to have millions of solar panels destined for landfills, unless we build now with the end-of-use cycle. This is an issue the industry is aware of but solid solutions are slow to be implemented.

- Addressing society’s high use of energy. This phenomenal study by Thea Riofrancos explores how the US could make the shift without extensive mining. The authors write, “This report finds that the United States can achieve zero emissions transportation while limiting the amount of lithium mining necessary by reducing the car dependence of the transportation system, decreasing the size of electric vehicle batteries, and maximizing lithium recycling.”